“‘I think I shall go back to mother,’ he said timidly.

‘Good-bye,’ replied Solomon Caw with a queer look.

But Peter hesitated. ‘Why don’t you go?’ the old one asked politely.

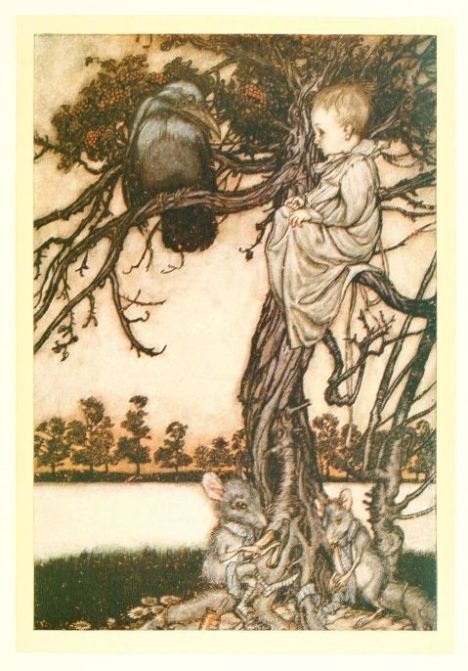

‘I suppose,’ said Peter huskily, ‘I suppose I can still fly?’

You see he had lost faith.

‘Poor little half-and-half!’ said Solomon, who was not really hard-hearted, ‘you will never be able to fly again, not even on windy days. You must live here on the island always.’

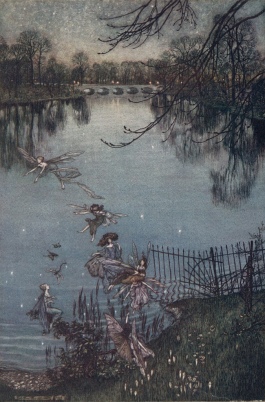

‘And never even go to the Kensington Gardens?’ Peter asked tragically.

‘How could you get across?’ said Solomon. He promised very kindly, however, to teach Peter as many of the bird ways as could be learned by one of such an awkward shape.

‘Then I shan’t be exactly a human? Peter asked.

‘No.’

‘Nor exactly a bird?’

‘No.’

‘What shall I be?’

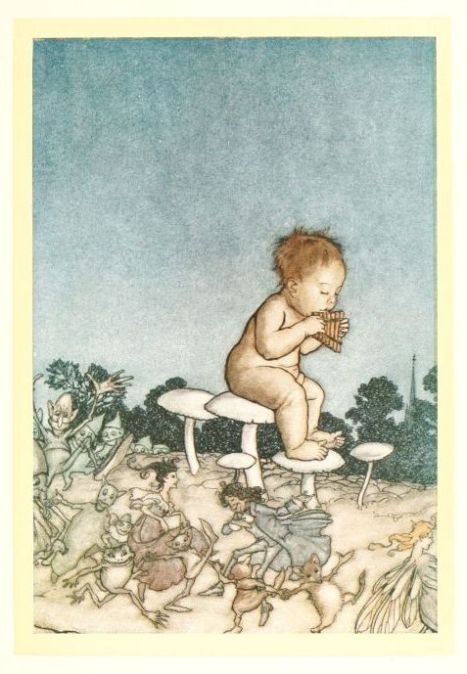

‘You will be a Betwixt-and-Between,’ Solomon said” (16-17).

This passage from J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, when analyzed, is found to supply us with a general portrayal of the entire novel. We see a boy named Peter Pan who, at first, longs for his mother, then realizes he can’t ever again fly. We further get a general idea of Barrie’s style of writing — the reader is also addressed directly using the word “you.” Finally, Peter Pan also learns from the very wise bird, Solomon, that he is neither human nor bird, but rather a “Betwixt-and-between.”

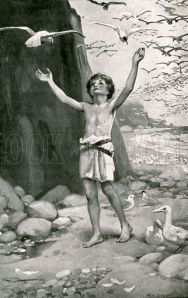

Firstly, we see an unsure Peter Pan; a little baby who’s only 1 week old (which is absurd — I shall get into that shortly) and has recently flew away from his mother’s company, already regretting his departure. Indeed, in the passage above, Peter Pan is very willing to go back, if only he was able to fly. Of course, Peter Pan lost faith in his ability to fly so he is never again able to do so. This, of course, is a powerful message that shows the empowerment of self-confidence and how crucial it is to be sure of yourself if you ever wish to conquer and accomplish your aspirations — or even your flaws. This is described earlier in the text just after Peter Pan flew from out his window, “It is wonderful that he could fly without wings, but the place itched tremendously, and–and–perhaps we could all fly if we were as dead-confident-sure of our capacity to do it as was bold Peter Pan that evening” (13). How beautiful is this? To be a child reading this line, the child would be consumed by wonder, amazement, and inspiration. Because I’m grown up and have been told repeatedly by others that I can’t “fly” among other things, the inspirational impact this line has on me is minimized, but I can only imagine its limitless impact on a young, fresh mind.

Throughout life, more specifically in school, a child — any child — will be faced, one time or another, by people who tell that child that he or she cannot aspire to do certain things or be a certain somebody, and eventually the child will start questioning his or her own abilities, potential, and capacity. This is another reason why the Peter Pan series is such a classic; Peter Pan may be told now, by Solomon, that he will never again fly, but inevitably Peter Pan succeeds at just that and much much more! A book is a collection of mere thin pages and ink imprints, but the worlds that are detailed will take any reader on an incredible adventure that defies all the ifs and buts we are faced with in reality; another reason why fiction writing, in particular children’s literature, is essential to our society.

From this passage, we also get a feel for Barrie’s inclusion of the reader as a character in the story. he does this with the line, “You see he had lost faith,” which tells us directly (evermore emphasizing the importance of faith) and also asserts that this story is for “you,” and that this story was written by many of “you.” As we see in chapter 1, “The Grand Tour of the Gardens,” the narrator/writer of this novel is also a character in the story, “[The Kensington Gardens] are in London, where the King lives, and I used to take David there nearly every day” (3). The use of the personal pronoun, ‘I’, declares substance to the narrator, thus the use of ‘I’ and ‘you’ reenacts a sort of story telling involving a storyteller (I) and its audience (you); a situation where a child feels comfortable and delighted to have, perhaps a parents, sharing to them a story. Barrie further captures the heart and attention of the child reader through his inclusion of David as a character in the story; though, he is the most relatable character because David is also joining in on the listening of the story — Barrie even taking it one step further by having David as an accompanying storyteller in which the story manifests from both the adult narrator’s perspective and that of a child’s (David),

“I ought to mention here that the following is our way with a story: First I tell it to him, and then he tells it to me, the understanding being that it is quite a different story; and then I retell it with his additions, and so we go on until no one could say whether it is more his story or mine” (13).

The intended audience being a child reader, thus the inclusion of a child’s voice in helping tell the story gives it more authenticity than most other texts of children’s literature.

Finally, as we see in the passage above, Peter Pan learns from the very wise bird, Solomon, that he is neither human nor bird, but rather a “Betwixt-and-between.” Peter Pan is seemingly incapable of declaring his identity. This absence of identity is discussed in this week’s assigned essay, “The Riddle of His Being: An Exploration of Peter Pan’s Perpetually Altering State,”

“Peter Pan changes shape and position so often that he is uncertain about his identity. Wendy is the first to ask Peter Pan what he is but he cannot answer. His responses to Wendy’s question are vague and abstract” (McGavock).

This brings me back to Peter Pan’s absurd age of only 1 week old. This also brings me to many questions such as: how is Peter Pan so intelligent at so young an age? How is he able to speak nearly perfect English so fluently? How does he know braveness but not fear? Such observations baffle me, and I am forced to categorize such as the work of fiction; not to be questioned. It is believable that because of his young age that he is unable to see himself as human when he was so recently a bird, but these matters of self-identity and self-discovering are usually associated with teens and young adults who are trying to find out who they are (it was only until recently until I discovered such myself!). Poor Peter Pan, I wish him all the best, but for a boy of 1 week old who will never grow up… I pity him; though, I envy all his faith through his adventures — and many at that.