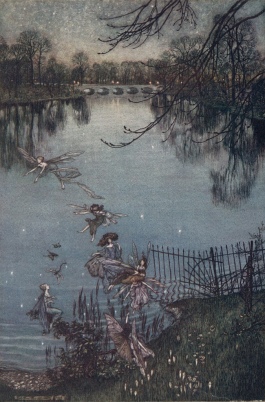

Two of the books we have read recently, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Five Children and It, are both lesser-known works today, especially when compared to some of the other novels we have read this semester. While the character of Peter Pan is well known, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens was overshadowed by the more popular Peter and Wendy. While Five Children and It has endured as a classic in England, it is recognized far less in the U.S. While there are certainly several reasons for the lower status of both of these books, one reason that has been suggested by several people in the class is the specificity of the place or the culture in which the books are set. Peter Pan takes place in Kensington Gardens, a distinct landmark that would have been unfamiliar to American readers. Likewise, Five Children and It is grounded in British country life and a culture that may have seemed strange to American children.

Two of the books we have read recently, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Five Children and It, are both lesser-known works today, especially when compared to some of the other novels we have read this semester. While the character of Peter Pan is well known, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens was overshadowed by the more popular Peter and Wendy. While Five Children and It has endured as a classic in England, it is recognized far less in the U.S. While there are certainly several reasons for the lower status of both of these books, one reason that has been suggested by several people in the class is the specificity of the place or the culture in which the books are set. Peter Pan takes place in Kensington Gardens, a distinct landmark that would have been unfamiliar to American readers. Likewise, Five Children and It is grounded in British country life and a culture that may have seemed strange to American children.

Upon learning from the group presentation on Tuesday that The Secret Garden faded in popularity after its initial publication, I immediately wondered if the same problem of location could be at fault in this case. After all, the book seems to be tied closely to its English setting. Most significant are the frequent descriptions of the remarkable landscape of the moor. The moor is so present in the story that reviewer R. A. Whay remarked that “it might be the moor, the Yorkshire moor…that is to be accepted as the protagonist” (Whay 269). American readers were likely not familiar with this landscape or the “cool and warm and sweet” (Burnett 108) wind off of the moor that has such a powerful effect on Mary and Colin.

After reading Anne Lundin’s essay on the reception of the book, however, it does not seem that the specific setting of the story had any significant effect on its popularity or lack thereof. This led me to wonder why the specificity of the location did not have the negative effect on The Secret Garden that it had on other books, and I think that the answer lies in the garden itself. The secret garden is a hidden, magical sort of place that is disconnected from the rest of the gardens and from Misselthwaite Manor. The garden is not tied to a specific time or place, and when Mary, Dickon, and Colin are in the garden it is as if they have left the outside world and entered an entirely separate place. The garden exists as an equivalent to Wonderland or Neverland, a mystical world into which all readers can imagine themselves. The “mythic imagery of a restored garden, of something submerged awaiting discovery” (Lundin 287) can appeal to everyone, thus outweighing any negative effect that the specific location may have.

After reading Anne Lundin’s essay on the reception of the book, however, it does not seem that the specific setting of the story had any significant effect on its popularity or lack thereof. This led me to wonder why the specificity of the location did not have the negative effect on The Secret Garden that it had on other books, and I think that the answer lies in the garden itself. The secret garden is a hidden, magical sort of place that is disconnected from the rest of the gardens and from Misselthwaite Manor. The garden is not tied to a specific time or place, and when Mary, Dickon, and Colin are in the garden it is as if they have left the outside world and entered an entirely separate place. The garden exists as an equivalent to Wonderland or Neverland, a mystical world into which all readers can imagine themselves. The “mythic imagery of a restored garden, of something submerged awaiting discovery” (Lundin 287) can appeal to everyone, thus outweighing any negative effect that the specific location may have.

All quotes from:

Burnett, Frances H, and Gretchen Gerzina. The Secret Garden: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Contexts, Burnett in the Press, Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006. Print.