In Kelly Hager’s article, “Betsy and the Canon,” she explores the role of novels in the formation of the canon, and how the novels turn their audience into good readers. Hager uses the Betsy-Tacy series and Alcott’s Little Women as her primary examples, showing how various characters influence what books the protagonists read. These characters, although fictional, have had a hand in the formation of the canon, through their selections of works for the protagonist.

These selections include such works as, Tales from Shakespeare, Don Quixote, Gulliver’s Travels, Tom Sawyer, Ivanhoe, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Oliver Twist, The Grapes of Wrath, Animal Farm, Plutarch’s Lives, Pilgrim’s Progress, and other works by the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, and William Faulkner.

These works are deemed “acceptable” for young girls to read. But what most of them have in common is that they were not necessarily written with children as the intended audience, and none of them speak to children as less intelligent than adults–none of them speak down to them. Why, then, are they “acceptable” reading for young children? Shouldn’t children read books that are for children? Aren’t these all books for adults? The Grapes of Wrath, for instance, has several deaths, and ends with a woman breastfeeding a grown man, and Gulliver’s Travels deals with such subjects as public urination. I could speak for months on the inappropriateness of William Shakespeare (among the least racy of his credits is the invention of the “your mom” joke).

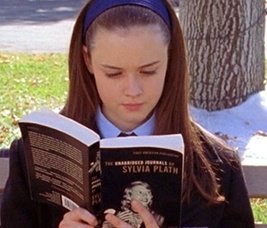

My argument is that these books are appropriate for children specifically because they do not speak down to them. They actually prepare children for reading and writing in the adult world, not to mention teaching them how to interact with other people. The books do not treat children as if they are less intelligent that adults, but rather expect them to learn the reading skills required of an adult–looking up words in the dictionary, using context clues, and, in extreme cases, dealing with adult topics such as death and sex.