The term “literary canon” is widely used in reference to a group of literary texts that are considered the finest or most important representations of a particular place or time period. A literary canon can be comprised of works written in the same country or region or within a specific time period; in this way, a canon establishes a collection of related literary texts. While literary works can of course be classified in many different ways (i.e. by theme, region, time period, topic, etc.), inclusion in the literary canon seems to apply a certain legitimacy or authority to a literary work.

As we saw in Kelly Hager’s article, the canon is largely a product of our literary upbringing, or what we read as children. We are told by our parents, our librarians, and our teachers to read the “classics,” and we do so, therefore perpetuating both their validity and popularity and securing their place in the literary canon. However, with the increased use of technology and media in the 20th century, we have seen a shift in literary influence, now coming not only from books but from television and cinema, as well, though the same end is still met.

For example, Hager describes an instance during which Betsy of Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books is encouraged to spend a “splendid” day exploring the library. This sentiment is one that is encouraged in many children’s television programs today, as well. One distinct memory I have from my childhood is the song sang during the episode “Arthur’s Almost Live Not Real Music Festival” of the popular children’s show Arthur that encourages that encourages kids to explore the classics at their public library, mentioning authors such as Jules Verne, H.G Wells, and Ray Bradbury.

The popular children’s television series Wishbone encouraged children to read the classics, as well. This show featured a talking dog by the same name that often daydreamed that he was the lead character in a classic literary work. Each episode portrayed a different text, and the show drew parallels between the stories’ events and the lives of Wishbone, his owner Joe, and Joe’s friends, making the classics interesting and relatable to Wishbone’s audience.

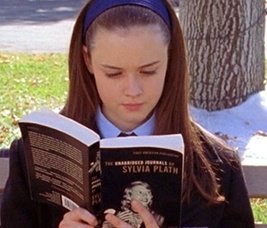

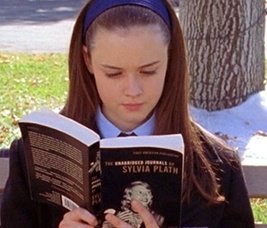

While the two examples I have provided are specifically targeted toward children, television as a vesicle of canon perpetuation can be seen in shows geared toward adolescents, as well. The clearest example of this I think is the popular show Gilmore Girls that ran from 2000 through 2007. This show was a drama-comedy series about the close relationship between a single woman and her extremely bright daughter Rory, living in the fictional town of Stars Hollow, Connecticut. Each episode featured Yale-bound Rory living her life, always with at least one book on hand. From Little Women to Don Quixote, Crime and Punishment to The Bell Jar, she was constantly shown reading in a corner, on a bus, at the park, wherever she may find herself. This show developed somewhat of a cult following. Soon after, “Rory Gilmore Reading Challenges” began surfacing all over the Internet, and many girls took Rory’s literary lead and began working through the list.

While the influence of teachers, parents, and librarians on what children and adolescence read has continued and will continue to perpetuate the state of the literary canon(s), it is clear that popular entertainment and media have begun to take on some of this responsibility, as well. I think it will be interesting to see how the dynamics of this continues to shift and change as our culture becomes more and more entrenched in entertainment and media.

currentVote

noRating

noWeight