The Looking-Glass world that Alice enters in Through the Looking-Glass (And What Alice Found There) is undoubtedly a creation from the logical mind of Charles Dodgson. It is described as having “a number of tiny little brooks running straight across it from side to side, and the ground between was divided up into squares by a number of little green hedges, that reached from brook to brook.” This description is obviously a chessboard, which is a theme throughout the story. Alice encounters all of the pieces in the chess game that help her, a pawn, to reach the other side of the board and become a queen herself within 11 moves.

Being a thorough man, Dodgson included a picture of the chessboard in the Looking-Glass world of the moves that are made in the story in the exact order they take place.

Alice begins her journey upon meeting the Red Queen at the forefront of the white piece’s side of the chessboard, who then allows her to be a pawn for the white team. The Red Queen tells Alice, “you’re in the Second Square to begin with: when you get to the Eighth Square you’ll be a Queen.” In the above picture we can see Alice begins as a pawn in the second square for move number one. Next, Alice “ran down the hill and jumped over the first of the six little brooks,” which puts her in the Third Square. After this sentence, we see three rows of asterisks, which are used throughout the story to signify that Alice has moved into the next square.

Alice then rides an unusual railway that jumps across a brook, sending Alice into the Fourth square, which is the home of Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum. After their discourse and poems she meets the White Queen, and she follows after her across a brook, which takes her into the Fifth Square. To her astonishment, the queen becomes a sheep, and the surroundings become a small shop of goods. She suddenly realizes she’s on a boat and rows through this square. At the end, she’s in the small shop again and she jumps across a small brook in the shop into the Sixth Square.

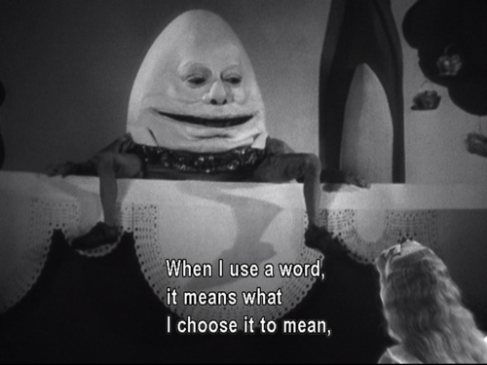

In the Sixth Square, Alice has a pedantic lesson with Humpty Dumpty, who teaches her the imaginative aspect of language. Leaving him, she meets the White King and his soldiers and encounter a problem regarding Plum Pudding and a group of strange animals. After leaving the Lion and Unicorn behind, Alice enters the the Seventh Square.

In the Seventh Square, Alice is almost taken by the Red Knight. However, The White Knight comes to her aid, takes the Red Knight, and accompanies Alice to the edge of the Eight Square.

At this point, Alice jumps across the final brook and suddenly is crowned a queen. This is not the end of the game though.

Alice then attends her own coronation dinner. The Red Queen and all other attendants aggravate Alice to the point where she throws a tantrum. In her fury, Alice grabs the Red Queen and shakes her, taking the piece and winning the game.

Thus, in eleven total moves, Alice moves across the chessboard as a pawn and becomes a queen. She then takes the Red Queen and wins the game. The only issue, which even Dodgson confesses, is that the sides take their turns out of order. However, the actual moves can be mapped out and recorded as Alice journeys across the Looking-Glass world. Such a complex scheme truly proves Dodgson to be a logic-loving and mathematical genius because one can read this novel through the distant view of a chessboard.