As per our discussion in class, Lewis Carroll–through the agent of his characters–was able to insert a philosophy of language and literary comprehension. Humpty Dumpty most explicitly demonstrates this throughout his interaction with Alice, when she reveals her confusion and the difficulty of understanding the poem “Jabberwocky” presents her. Humpty Dumpty swiftly informs her that he deconstruct the ambiguity of the words (and of course goes on to translate an entire stanza).

Humpty Dumpty is actually discussing the linguistic side to Alice’s encounter with the surreal. Her wonderland/looking-glass world does exist under the same conditions as “the real world,” therefore, the semantics and pragmatics of language there would not follow the same rules.

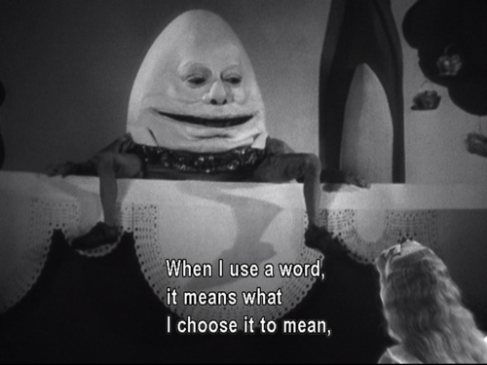

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’ ” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’ ”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument’,” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master that’s all.”

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. “They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!”

I brought up the point that perhaps Carroll was trying to illustrate that meaning is subjective to the individual, and that when reading the text, the reader should also be applying their own meaning, unadulterated by others opinions. Carroll deliberately wrote “Jabberwocky” to be an interactive work, so that readers wouldn’t be subjected to a poem that already had an abundant amount of interpretations (which it still does), but by using nonsensical words instead, no one could fully claim they knew what the intended meaning was.

The conversation between Alice and Humpty Dumpty also address the connection between language and reality. Throughout Alice’s adventure, she confronts the problem of existence and the true nature of things as a result of the altered label she is no longer familiar with. Conceptually she is able to conjure an image of whatever is being discussed, but she is consistently disoriented by the skewed definitions, and the arbitrary nature of the conversations she finds herself participating in.

Humpty Dumpty explains to Alice that he makes up the definitions of the words he uses, which would indicate a complete irrelevancy to any message he was trying to convey–except the message Carroll is conveying through Dumpty, which is (in part) an understanding of human expression through language.