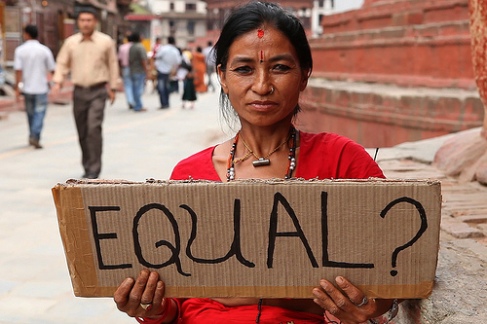

J.M Barrie’s Peter Pan has endured in the hearts of both children and adults since he first appeared in Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. Though this character has served as a classic symbol for childhood and children’s literature, he also indicates a much more racist period in culture and history.

“The Great White Father” was the working title of the original play by J.M. Barrie. This references racist elements of the story Peter Pan and Wendy and of Peter’s character. Though the play’s producer ultimately rejected this title, the term “redskin,” borrowed from United States racial jargon, was still used in the play to specify indigenous populations. The way that Barrie depicts the indigenous characters, too, denotes stereotypically savage behavior of an aggressive tribe out to wreak havoc on the Lost Boys, a group of young white children, when they think the Boys snatched the chief’s daughter.

Interestingly enough, it seems that more recent adaptations have sought to address and correct such blatantly racist implications. The 2003 film adaptation Peter Pan provides one example of this. In the original book and play (and most adaptations) the characters Wendy and Tiger Lily often stand in direct contrast. Even though they are both women, and depicted as weaker than Peter, Wendy is presented as stronger and more intelligent than Tiger Lily, her indigenous counterpart. Tiger Lily, on the other hand, is very helpless and has hardly anything (intelligent or otherwise) to say. In Peter Pan (2003), however, Tiger Lily, played by an Iroquois actress, does not play into this earlier established stereotype. Instead, she is depicted as a fiery, defiant young lady, who stands her ground against Captain Hook. She even contrasts her original damsel-in-distress depiction and actively saves John Darling from a band of pirates.

While there are racial tensions that will never be able to be completely taken out of Peter Pan adaptations without changing the story, recent adaptations, such as 2003’s Peter Pan successfully combats some of the racial prejudices illustrates in Barrie’s original book and play.