In Carroll’s Through The Looking-Glass, as well as his first book, there is a consistency of characters questioning everything Alice says, or correcting her; more so in Through The Looking-Glass, I find. It is a motif that spans both stories to the very end, and, for me at least, can make me nauseous at times, due to the literalness and word-picky characters in his stories. For poor Alice, I hardly know how she bears with it all, constantly having her words and sentences reevaluated and given meanings she hadn’t first meant, then being told that she should have said what she meant; which I’m sure, if she had said exactly what she meant, it would have been questioned and evaluated just as harsh.

Some major instances of this motif in Carroll’s Through The Looking-Glass are the scenes when Alice meets the red queen, Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the white queen, and Humpty Dumpty.

With the red queen, Alice says that she lost her way, in which the queen replies, “‘I don’t know what you mean by your way,’ said the Queen: ‘all the ways about her belong to me.'” For poor Alice, such a reply would be considered extremely rude an outbreak, especially in the social aspects of England at the time. Alice is simply saying a normal utterance: that she lost her way. Like most all the people of Wonderland and in the Looking-Glass, the red queen takes this literal, and, because she is a queen (and very ignorant, I may add), she automatically assumes Alice is claiming that all the ways are her’s.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee are much worse to her though, suggesting that, because the red king is perhaps dreaming of Alice, that she doesn’t really exist — that she couldn’t exist in two places at once. Instead of messing with the very words she speaks, they mess around with her logic, convincing her, to a point, that she is not real!

“‘And if he left off dreaming about you, where do you suppose you’d be?’

‘Where I am now, of course,’ said Alice.

‘Not you!’ Tweedledee retorted contemptuously. ‘You’d be nowhere. Why, you’re only a sort of thing in his dream!’

‘If that there King was to wake,’ added Tweedledum, ‘you’d go out–bang!–just like a candle!'”

Poor Alice, this even provokes tears in her eyes. This is a clear example of the cruel nature of the characters in Carroll’s books; perhaps they don’t mean to be cruel, since their logic is based off of nonsense and a common theme: that we rely so much on language to convey meaning to everything, that if those meanings are meddled or messed with, our existence shrivels up to the size of a useless, slugging snail.

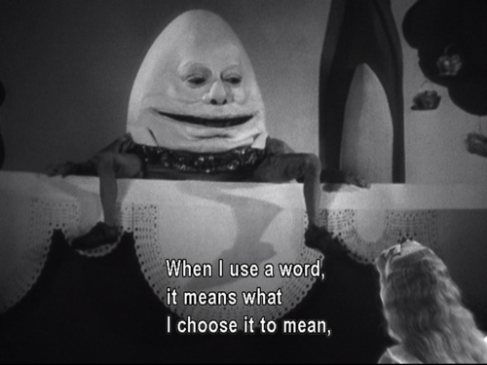

The last scene I want to note, is that of Alice meeting Humpty Dumpty, who may just be the worst of them all, in terms of messing with Alice’s words. When Alice tells Humpty Dumpty her name, he follows with, “‘It’s a stupid name enough!'” Then asks what it means. Of course, Alice doesn’t understand why a name must mean something. Humpty Dumpty declares that it does, in fact; that his own name describes his own shape and good looks quite well. Similarly, Alice tells him her age, “‘Seven years and six months.'” Humpty Dumpty, of course, tells her that she’s wrong, that if he meant how old she was (which he pretty much did), then he would have said it. Then he says that her age is better left off at seven, then further messes with her words.

Poor Alice, such interactions could make one go mad. Clearly, Carroll meant all this upon the reader; it creates an atmosphere of nonsense, which is entertaining to children because it can be funny at times, and they don’t have to use much of their brain to get it. For me, I find it entertaining but at the same time, a bit angry at the characters and wanting to put an end to their nonsense, for some of it is so uncalled for. This is the motif in Carroll’s books. It works. It is original. It is a classic, with an everlasting place in our society.